He was to spend the last two decades of his life in his country house near Vernon, downriver in the depths of the green Normandy countryside. But many of his crucial years were spent closer to Paris, and many of his formative artistic and personal relationships date back to times near or on the river.

Monet moved to Argenteuil in late 1871. Formerly a sleepy village, it was to become a popular destination for the Parisian middle classes, who took advantage of their growing affluence, and the arrival of the railway, to enjoy the excursions and holidays that had once been reserved for the wealthy. A place of promenades, boating trips and bathing parties, it was nonetheless still affordable for the impoverished Monet, now living with his wife and one-time model Camille Doncieux.

As Monet slowly began to achieve some commercial success, he bought a tiny boat and equipped it as a water-studio from which he would work, sometimes alone and sometimes accompanied by Camille. Here, away from the day-trippers, he had the time and space to explore a world of light and colour.

Since at least the 1860s, Monet had worked more and more “en plein air”: painting directly from an outdoor view, to better emphasise the qualities of light and atmosphere in the moment, rather than using minor sketches or studies, or working entirely in the studio.

Though other contemporaries did the same - Renoir and Sisley in particular – Monet was particularly committed to this approach. Manet and Sargent were among the artists who captured him at work, in the fields or on the water. It is easy to imagine him in his floating studio, capturing the moment of “Morning on the Seine”. His approach may also have been influenced by a visit to London in 1870, where he saw the works of one of the most committed and pioneering artists en plein air: JMW Turner.

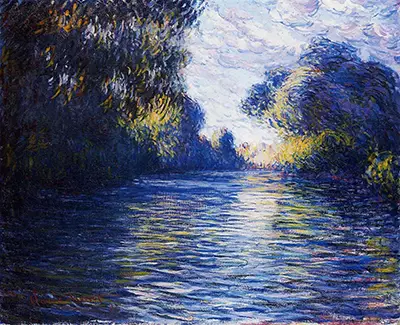

To those more familiar with the softness and almost ethereal quality of some of his studies of waterlilies, “Morning on the Seine” may come as a surprise. Darker, stronger brushstrokes through the water and in the foliage to the left might even call to mind similarly pronounced strokes of colour used by Van Gogh, and the pinkish purple of the clouds stands out clearly against the sky. Typically, it is an intensely and accurately realised study of the impressions of colour.

It is no coincidence that the painting has come down to us with the title “Morning on the Seine”. Monet famously returned to subjects and locations again and again, studying the different effects of light at different times of day. Thus, his famous Haystacks appear shadowed with cold, deep blue, almost frosted with brilliant white light, burning with intense oranges, or touched with red.

Similarly, this is just one treatment of the impressions of light and colour on the Seine. “Morning on the Seine in the Rain” shows an even more impressionistic rendering of a similar scene, in blues and greens, while “Morning on the Seine, near Giverny”, painted in the same year, shows a shadowy, misty scene of soft colours - dark trees and foliage, and a pale, dawning sky.